TLDR: A large German survey of 10,339 adults finds that most people have heard of ultrasound and EEG, but fewer know about brain stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, fMRI, and especially brain-computer interfaces. Prior exposure, work in health care, and higher health literacy track with greater self-reported knowledge, while gaps appear across age and gender.

Neurotechnology now touches clinical care, consumer wellness, and popular culture. The study summarized here set out to measure who has heard of six representative technologies and how much they say they know. The six were ultrasound, EEG, fMRI, brain stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, and brain-computer interfaces.

What The Survey Did

Researchers fielded a nationwide web survey in Germany with a final analytic sample of 10,339 adults, balanced on key demographics. Respondents rated whether they had heard of each technology and, if so, how much they knew. The team also collected information on prior use, jobs in health care, health literacy, stress, religiosity, and demographics.

What People Know Today

Figure 1 offers the top-line view. Almost everyone reported at least some knowledge of ultrasound at 94.8 percent. Awareness then steps down through EEG at 79.9 percent, brain stimulation at 65.6 percent, fMRI at 60.5 percent, spinal cord stimulation at 58.8 percent, and BCIs at 47.3 percent. Among those who had heard of them, many selected “very little” for brain stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, and BCIs, underscoring that awareness often lacks depth. Knowledge across categories correlates positively, suggesting shared antecedents such as health exposure or general tech interest.

What Shapes Those Differences

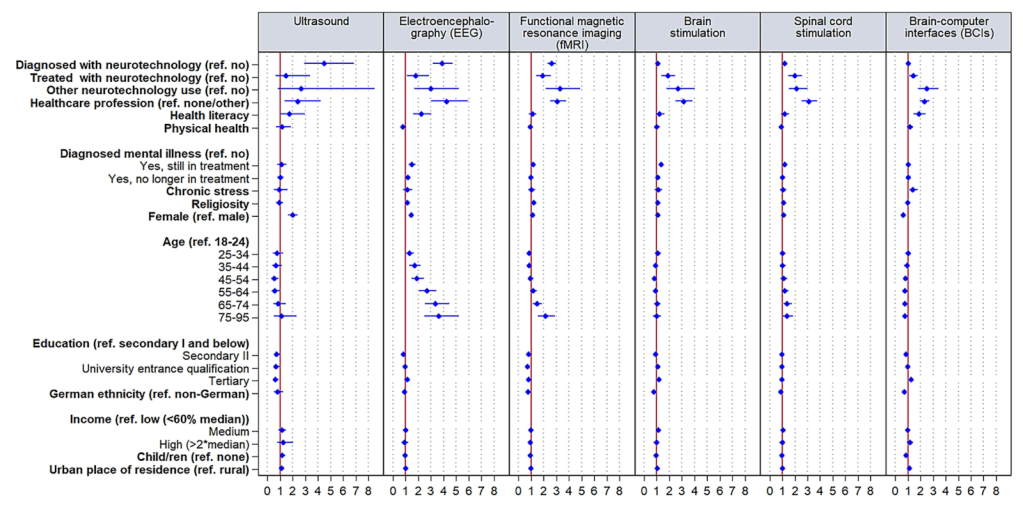

Figure 2 models who is more likely to have heard of each technology. Prior diagnostic use shows large odds for ultrasound and EEG and moderate odds for fMRI. Treatment experience adds smaller but positive odds for EEG, fMRI, brain stimulation, and spinal cord stimulation. “Other” uses, such as nonmedical applications, show medium positive effects across the board and a large effect for fMRI. Working in a health-care job is a strong predictor across technologies.

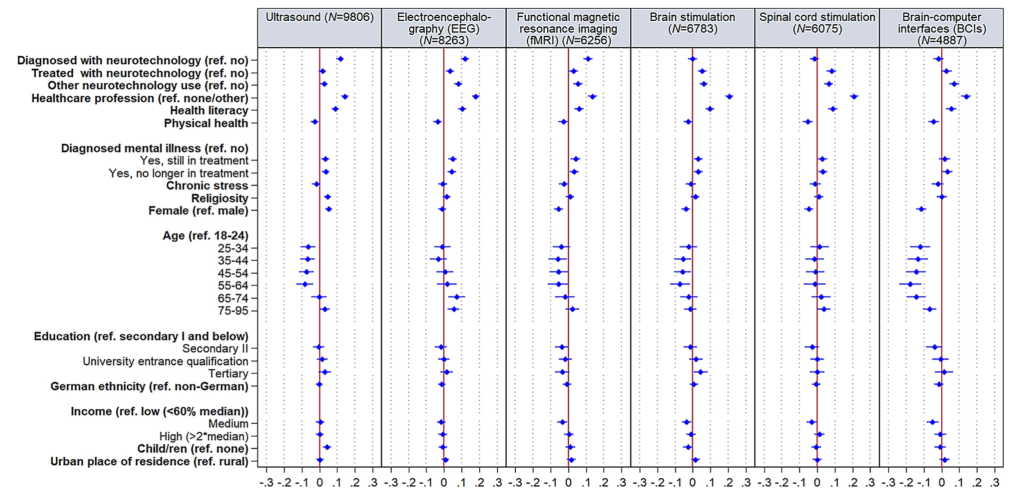

Health literacy matters as well. Higher literacy increases the likelihood of reporting some knowledge for ultrasound and BCIs and has a medium effect for EEG. Among those who know at least a little, Figure 3 shows that diagnostic exposure to ultrasound, EEG, or fMRI nudges the self-rated level upward, and health-care employment again tracks with more knowledge.

Where Gaps Appear

Gender and age patterns emerge. Women are more likely to report knowledge of ultrasound but less likely for BCIs, and among those with some knowledge they rate lower on BCIs. Knowledge of EEG tends to decline with age, while the oldest group is more likely to report familiarity with fMRI than the youngest. Education shows few effects except a lower likelihood of ultrasound familiarity among the most educated groups compared with the least. Ethnicity, income, children, and rural versus urban residence show no substantial effects.

Why This Matters

Knowledge is a precursor to informed decision-making and technology acceptance, yet awareness without depth can still leave room for misconceptions. The pattern here points to practical levers. Clinicians, patient groups, and developers can raise the floor with plain-language explainers, point-of-care materials, and targeted campaigns for populations with less exposure, while building on natural touchpoints where diagnostics already occur.

Kenneth’s opinion

This paper is valuable because it moves beyond anecdotes and quantifies where understanding begins and where it stalls. The biggest opportunity is at the interface between first contact and durable comprehension. Health systems and device makers should treat “I have heard of it” as a starting point, not an endpoint, and pair routine tests and referrals with short, repeated explanations that link the name of a technology to its purpose, benefits, and limits. That approach would likely narrow the BCI gap, reduce anxiety around stimulation methods, and improve consent quality.

FAQ

1) What exactly counted as “neurotechnology” in this study?

Ultrasound, EEG, fMRI, brain stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, and brain-computer interfaces.

2) Who was surveyed and how large was the sample?

A nationally balanced German adult sample with 10,339 analyzable responses.

3) Which technologies had the highest and lowest awareness?

Highest was ultrasound at 94.8 percent and EEG at 79.9 percent. Lowest was BCIs at 47.3 percent.

4) What factors most increased the odds of having heard of a technology?

Prior diagnostic use, health-care employment, and health literacy. Treatment and “other” uses added smaller positive effects depending on the technology.

5) Where are the main disparities?

Women report more knowledge of ultrasound but less of BCIs. EEG familiarity declines with age, while the oldest group reports more fMRI knowledge than the youngest. Many other social factors show little or no effect.

Source: Sattler S, Mehlkop G, Neuhaus A, Wexler A, Reiner PB. Exploring disparities in self-reported knowledge about neurotechnology. Scientific Reports, 2025.

Leave a comment