TLDR

This 2019 review argues that the vagus nerve sits at a practical control point in brain to gut signaling because it is mostly sensory input to the brain and it also carries output that can dial down inflammation. It outlines two main anti-inflammatory routes, one through HPA axis cortisol and one through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, then connects those mechanisms to early clinical signals in Crohn’s disease and to the growing menu of invasive and noninvasive stimulation devices.

What this paper is

Bonaz, Sinniger, and Pellissier wrote a review on vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) “at the interface of brain–gut interactions.” It frames VNS as a bioelectronic, nondrug approach for GI conditions where brain–gut communication is dysregulated, with emphasis on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

A key starting point is anatomy. The vagus nerve is described as a mixed nerve with roughly 80% afferent fibers and 20% efferent fibers, meaning it is largely a “gut-to-brain” information highway that also has a smaller “brain-to-gut” control channel.

Why the vagus nerve is interesting for intestinal disorders

The authors tie vagal tone to inflammatory and functional GI disease patterns. They note that heart rate variability (HRV) at rest reflects parasympathetic vagal tone, and that low HRV (low vagal tone) shows up in IBS and IBD and is linked (in cited work) with higher circulating inflammatory markers such as TNF-α in Crohn’s disease and higher epinephrine in IBS. The implied therapeutic bet is simple: if low vagal tone tracks with worse physiology, boosting vagal signaling might help.

Three figures worth understanding

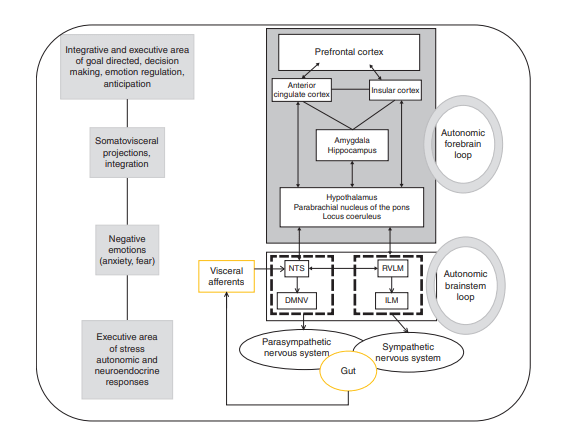

Figure 2: The brain–gut “control stack”

Figure 2 is the clearest map of how gut signals become brain decisions, and how the brain sends instructions back. Gut afferents from vagal and splanchnic pathways converge on the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), near the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV), which is the origin of parasympathetic vagal efferents. That creates a brainstem loop involved in motility, acid secretion, food intake, and satiety. A higher “forebrain loop” (insula, anterior cingulate, amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, prefrontal cortex) modulates the brainstem loop, which is one reason stress and emotion can change gut function in real time.

Why it matters for therapy: it explains why VNS might influence both “hard” endpoints (motility, secretion) and “softer” endpoints (symptom perception, stress-linked flares) through the same wiring diagram.

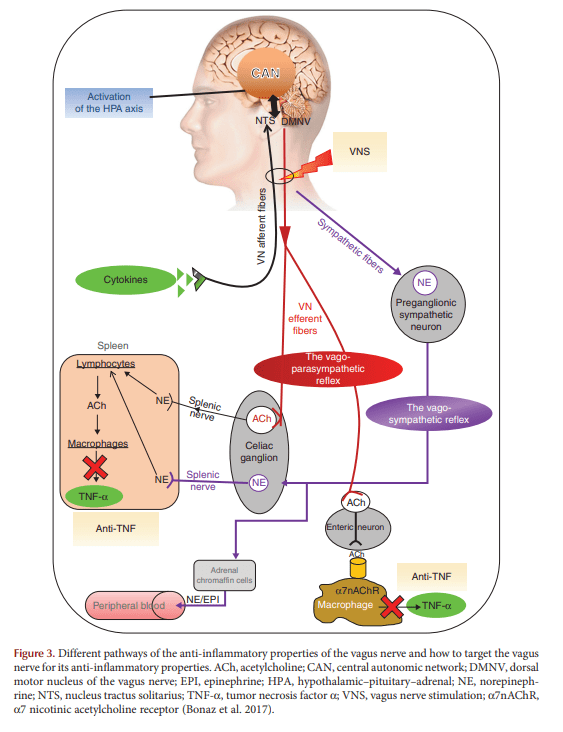

Figure 3: Two anti-inflammatory routes you are actually trying to trigger

Figure 3 lays out how the vagus nerve can reduce inflammation through (at least) two coordinated strategies:

- Afferent-driven endocrine braking: vagal afferents can engage central circuits that activate the HPA axis, leading to glucocorticoid release (cortisol) as a systemic anti-inflammatory signal.

- Efferent-driven immune modulation (CAP): vagal efferents are linked to the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, where acetylcholine signaling ultimately suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The review highlights α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as part of this suppression logic and depicts splenic involvement as one plausible relay.

Why it matters for therapy: it makes “VNS for gut inflammation” feel less like a vague wellness claim and more like targeted neuromodulation of immune outputs, with specific nodes you can measure (HRV, cytokines, clinical indices).

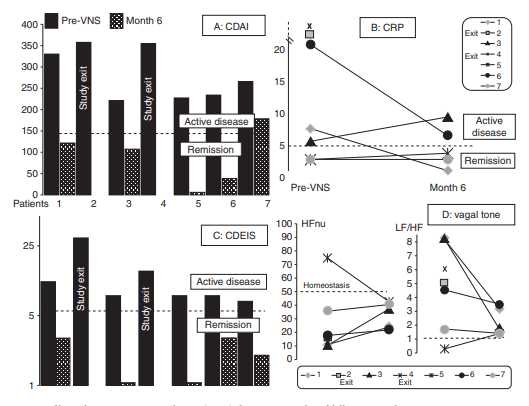

Figure 5: Early clinical signal in Crohn’s disease (small, but concrete)

Figure 5 summarizes a small pilot in active Crohn’s disease with 7 patients reported at 6 months (out of 9 enrolled) and a 1-year follow-up plan. Patients were selected using clinical activity (CDAI), inflammatory markers (CRP and or fecal calprotectin), and endoscopic severity (CDEIS). The figure tracks changes in CDAI, CRP, CDEIS, and autonomic markers of vagal tone and sympathovagal balance over 6 months, with remission cutoffs stated for each metric.

How to read it responsibly: this is not definitive efficacy evidence. It is a translational “does this look biologically plausible in people?” signal generator that the authors use to justify a future sham-controlled randomized trial.

Where the field is headed: invasive vs noninvasive VNS

The review distinguishes implanted VNS (validated historically for epilepsy and depression) from external devices that stimulate either the cervical vagus along the carotid axis or the auricular branch of the vagus in the ear (cymba concha), which projects to the NTS. It also lists two noninvasive devices used clinically in other indications: NEMOS (auricular electrode) and gammaCore (cervical stimulation discs).

cshperspectmed-BEM-a034199

For GI applications, the review’s tone is cautious. It notes limited published data in inflammatory GI disorders for noninvasive devices at the time, and it raises practical issues like adherence and consistent device placement.

cshperspectmed-BEM-a034199

Kenneth’s opinion

If you want vagus nerve stimulation to be taken seriously in gastroenterology, the path is straightforward and not glamorous: sham-controlled trials, clean physiological readouts, and clear patient selection. This review already hints at the right endpoints. Pair symptom scales with objective markers like HRV, CRP, fecal calprotectin, and endoscopic indices, then pre-specify what counts as response.

My bigger take is that the most interesting use case may be “stacked care,” not replacement care. VNS looks best as a tool to reduce inflammatory load, improve autonomic balance, and potentially lower flare frequency, while patients stay on evidence-based medical therapy when needed. The mechanism story in Figure 3 supports that kind of adjunct framing more than an all-or-nothing narrative.

FAQ

1) Is this paper a clinical trial?

No. It is a review. It summarizes mechanisms, preclinical work, and early human studies, including a small Crohn’s pilot.

2) What is the simplest way to explain why the vagus nerve matters here?

It is mostly sensory input from the gut to the brain (about 80% afferent fibers), and it also carries output that can shift immune signaling and gut function.

3) What are the two big anti-inflammatory mechanisms the authors emphasize?

HPA-axis driven cortisol release and the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway that can suppress cytokines such as TNF-α.

4) What did the Crohn’s pilot track as outcomes?

Clinical activity (CDAI), inflammation (CRP, and selection also used fecal calprotectin), endoscopic severity (CDEIS), plus autonomic metrics of vagal tone and sympathovagal balance over 6 months.

5) What noninvasive devices does the review name?

NEMOS (auricular stimulation) and gammaCore (cervical stimulation). The paper notes safety experience in other indications but limited GI inflammatory data at the time.

Source: Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Pellissier S. Vagus Nerve Stimulation at the Interface of Brain–Gut Interactions. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2019;9:a034199.

Leave a comment